Backgammon was first recorded as a ‘table game’ some 3000 BC in Persia. Later games tables and backgammon spread to Egypt, Mesopotamia, Rome and China in various guises. In medieval Europe the first ‘gaming tables’ appear in the 11th century as simple versions for the game of backgammon. Below is an illustration of a 14th century game in progress:

Board game 1628:

The 17th and early 18th century:

Curiously enough gaming tables were forbidden in England by law in Elizabethan times. A board game table (above) was excavated from a shipwreck dating from 1628 but by the 18th century gaming and gaming tables became part of everyday life. Huge numbers of card tables were produced during the 18th century many of which survive today.

A rare late 17th century style needlework topped tripod/gaming table can be viewed at

boxhouse-antiques.com (see image below). Needlework tops were practical for card games, keeping the noise of placing counters to a minimum and preventing accidental slippage of the cards. Some needlework panels were worked with images of cards and have recesses for counters and money.

The 18th and 19th century :

As the 18th century progressed gaming grew in popularity especially during the reigns of Louis X1V, XV and Louis XV1. Some examples had lobed outset corners for candlesticks. When not in use the hinged leg would allow the table to be folded away. Often the fashion was to take your gaming table with you to gambling sessions.

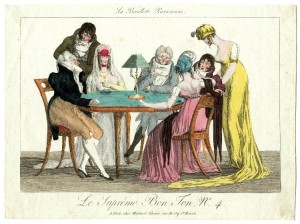

Queen Marie Antoinette 1755-1793 was a compulsive gambler and even had her personal gaming counters, ‘jetons’, contained in a pouch with the French Royal Coat of Arms embroidered on the lid. Huge fortunes changed hands at Versailles. The aristocracy in 18th century France were prohibited to engage in commerce so many aristocrats resorted to gaming ‘for a living’. Many lost their fortunes like the rather overweight ‘grande dame’ in this caricature. Sometimes whole estates were gambled away on the chance of a single card.

There is a vignette of the Queen’s life, and that of the King, in an account of a gambling session on the eve of the Queen’s twenty-first birthday in 1776:

‘Marie Antoinette cajoled Louis XVI into importing players from Paris who would act as bankers. Play started on the night of 30 October and continued to the morning of the 31st and went on again until 3 a.m. on the morning of the Feast of All Saints. When the King taxed his wife with this, she replied naughtily: “You said we could play, but you never specified for how long.” The King merely laughed and said quite cheerfully: “You’re all worthless, the lot of you!”’

‘It should be pointed out that the entire French royal family was prodigiously extravagant, seeing little connection between what they spent and what they had available to spend. This included the pious royal aunts, capable of using up 3 million livres in a six-week period. Then there was the Comte d`Artois, a noted spendthrift who regularly had his debts paid by his elder brother; these soon reached a total of 21 million livres. As for the Comte de Provence, he would have debts of 10 million livres paid by the King in the early 1780s.’

www.antoniafraser.com/antoinette.aspx

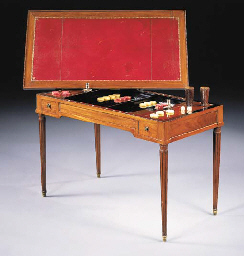

Below see a French Louis XV1 multi function-gaming/centre tables. These tables have reversible tops for backgammon and are sometimes referred to as ‘tric-trac’ tables, a French alternative term for backgammon.

At the end of the 18th century the game of ‘Bouillotte’ became fashionable in France. Both the purpose-designed table and accompanying lamp acquired their names from the game. These Bouillotte tables often came with marble tops and low brass galleries.

Look for the ‘bouillotte’ lamp in this early 19th century print. These lamps are much reproduced today, some with ‘tole peinte’ shades to direct light down onto the gaming table:

Pair of ‘Bouillotte lamps’:

In England too gaming was the rage in the 18th century and enthusiasts might like to dip into Francine Du Plessix Gray’s book “High Life Sex and Gambling in 18th century England”.

www.amanda-foreman.com/new-yorker.shtml“Also in great diversity were the tables which pandered to the 18th-century passion for gaming, which continued unabated until the Revolution. One of the panels of Huet’s Petite Singerie at Chantilly depicts monkeys in the costume of the day playing at cards,but card-tables apart, special tables for all kinds of games – chess, backgammon, roulette, and billiards – were placed wherever company gathered”. www.francetoday.com/articles/2012/05/14/la-grande-singerie.html

The numbers of surviving gaming/card tables in England are huge, witness to the obsession with gambling. It would be outside the scope of this article to cover more than a few. Perhaps the best examples date from the William and Mary 1689-1702 and Queen Anne periods 1665-1714. See below. Both have a double ‘gateleg action’ for supporting the tops.

Some multi-purpose triple-top gaming/tea tables survive such as the George II example below. It has one polished surface for serving tea and a baize lined surface for gaming. Within the ‘well’ of the table was storage space for cards and counters etc. Some were fitted with a secret drawer possibly for a pistol. These table usually come in mahogany or, if before 1730, probably in walnut. These are much sought after by collectors. The back leg swings with a ‘spacer’ to support the tops. On rarer examples both back legs pull out in a ‘concertina’ action, positioning a leg at each corner. A slide would be available for stability.

A mechanical writing/gaming table:

The ingenious table illustrated above allows the user to choose one of two surfaces, either for playing cards or for writing. When the writing surface is open, the user has access to a hidden nest of drawers, which pop up suddenly on springs, when a catch is released. It was made in Neuwied in Germany in about 1755-60 by Abraham Roentgen, a cabinet-maker who had spent some time in London in the 1730s, where such mechanical tables were first made. In London he also practised the technique of inlaying engraved brass plaques into furniture. For this table, he has based his central plaque on a figure of ‘Winter’, from an engraving by Gottfried Bernhard Göz (1708-1774), who was a fellow member of the Moravian Church, of which Roentgen was an active member. Roentgen became one of Germany’s best-known cabinet-makers and his son David, who carried on his workshop, became celebrated throughout Europe, selling in Paris and to the Empress Catherine the Great in St Petersburg.

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O63424/writing-and-card-roentgen-AbrahamIn the 18th century in England, major cabinet makers indulged their clients with a large range of options. Here is a wonderful Chippendale period gaming table. On carved cabriole supports with counter wells in the baize lined surface and reserves for candles. www.thechippendalesociety.co.uk/collection.htm. Ca. 1755.

The transition from the Regency to William IV and Victoria witnessed a shift into more elaborate card tables generally supported on a column and with a platform or heavy carved tripod base. Many of the Victorian period were produced in newly fashionable and abundantly available rosewood and walnut.

In Victorian times there was also the so-called ‘Loo’ table, possibly derived from a popular card game ‘lanterloo’ which dates from the 17th century. These ‘loo’ tables have round or oval tilting tops but today the name ‘loo table’ has expanded its meaning to encompass any large Victorian table that tilts. Below is a typical tilting table commonly referred to as a ‘loo table’ by the antiques trade.