Beech:

Quite hard and common wood chiefly used in chair making, seat rails, seat frames, bent chair backs. However beech is very vulnerable to attack in the sapwood by wood boring insects. Occurs commonly in England and Europe. American beech is quite different. Sometimes beech is stained to resemble mahogany.

Here are some beech logs felled in E Europe.

Camphor and cedar wood:

Has an aromatic fragrance as well as repelling insects and is used in lining of linen chests etc. Occurs mainly in China, the Middle East and in parts of SE Asia. Below is a typical camphor wood chest which you’re likely to encounter. Open the lid and inhale!

Cherry wood:

Hard and heavy, tight grained wood. Used in Britain for chair making and panels in the 17th and 18th centuries. Few have survived. Cherry is similar to maple. Used to a greater degree by early 17th and 18th century American Colonial cabinet makers for simpler rustic pieces such as dressers, highboys and lowboys etc. Cherrywood was available in the American colonies. Period American cherry wood furniture is much sought after and costly.

This photograph is of a cherry wood cabriole leg dresser base from about 1730.

Chestnut:

Its structure is similar to oak and of the same family. Fairly hard and sometimes mistaken for solid walnut. Usually occurs in the solid and is particularly found used in French Provincial furniture. Chestnut abounds in rural France. Also much used in outdoor furniture.

Elm:

Originated in Central Asia now worldwide distribution. Ravaged by ‘Dutch Elm Disease’ in England in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Much used in England in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries for making ‘country furniture’. Elm is a tough, often well figured wood but is susceptible to worm particularly in the sapwood. Pliant so used in bow making when yew was unavailable. Takes wax well resulting in a lovely patina. Sure to be rare in the future. There is an interesting painting by John Constable showing barge building in England using elm. Also much favoured by the Chinese in furniture making past and present.

Harewood:

Of the sycamore and maple family it is cut into veneers often resulting in very fine graining. Used in violin making (fiddle back) and in inlays to the finest of 18th century smaller furniture.

Sycamore when stained is called ‘harewood’.

Kingwood:

Grown in Brazil. Used in veneering in the 18th century. Prized by the finest French ebenistes in the 18th century. After exposure in time it can acquire a wonderful golden colour. Also much favoured by 19th century cabinet makers in France and England reproducing the 18th century styles in commodes, vitrines etc.

Purple Heart:

Native to northern parts of South America this wood is very hard, heavy and quite difficult to work. Mostly cut as veneers and sought after (as above) in particular by the French cabinet makers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Sabicu:

A rare wood from a large tree in Cuba. Extremely hard and heavy. Interestingly the stairs for the 1851 Great Exhibition were constructed in sabicu to withstand the millions of feet using the treads for the six months of the exhibition, showing little wear!

Not much furniture was made in sabicu, surviving items are quite rare. This photograph is of an ormolu mounted commode veneered in sabicu.

Laburnum:

The heartwood of the slow growing laburnum tree. Often cut vertically across the grain to produce interesting and varied round sections much favoured by the late 17th century cabinet makers to veneer chests and occasionally bookcases. The annual ‘rings’ produce the ‘oyster’ panels seen on early veneered furniture. Oystering also is derived from similarly cut walnut and used in the same way. Both laburnum and walnut oyster veneered items are sought after and costly. Laburnum is toxic.

This picture is an example of ‘oyster’ cut across the grain.

Mahogany:

Comes from wide geographical locations and varies tremendously in its characteristics, impossible to detail here. Mahogany used to occur in vast quantities throughout the Americas, Southern Mexico through Central America to Venezuela and N. Columbia. It also used to occur in Cuba and Santo Domingo, Brazil and Peru. I have been in Cuba and was shown what was claimed to be the only remaining specimen left! Huge quantities were exported as ballast on the returning sailing ships to England on the last leg of the ‘triangle’ trade of manufactured goods from England to Africa, slaves from Africa to the Americas and exotic woods, sugar and rum to England. Little real quality mahogany from the Americas is left, alas.

African mahogany occurs mainly in the Ivory Coast and Nigeria but is inferior in quality to mahogany from the Americas. African mahoganies are used today mainly cut as veneers.

Ceylon produces some mahogany as do some SE Asian countries, here often confused with similar hardwoods.

The first imports into England occurred in around 1720 but very rare items have been documented dating from the late 17th century. I have only ever seen one confirmed such example, a dated wainscot chair, in mahogany, on the open market.

Sometimes cheaper woods are stained to resemble mahogany, beech would be an example of this but is much less dense than real mahogany. Some SE Asian hardwoods are difficult to distinguish from mahogany and are at least as good and as durable. Some Asiatic padouk and ‘redwood’ is also hard to separate from mahogany and is much sought after in its own right.

Oak:

The traditional forests of England provided a vast supply of best quality mature oak. The parklands around the stately homes grew oaks which were used by the estate carpenters from medieval times to fashion into furniture and paneling.

There are a number of species covering evergreen oaks and deciduous oaks. The former thrives in southern England and the Mediterranean countries. There are a number of hybrid oaks and wild oaks.

The English oak is one of the longest living trees and is highly prized for its timber. Rufus, son of William the Conqueror, set aside a vast oak forest in S England, some of these trees have survived 1000 years.

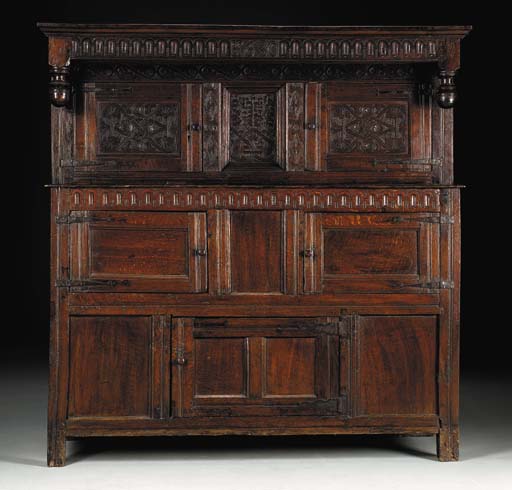

Oak was used almost exclusively for furniture making from earliest times up to the mid 17th century when walnut came into fashion used both in the solid and in veneering. Oak country furniture continued to be made for a considerable time thereafter. Many antique oak coffers survive as almost every household in England would have had one.

Much carcass construction is in oak. Oak can acquire a wonderful patination after centuries of polishing and exposure.

Padouk:

Similar in many ways to the rosewoods and is native to the Andaman Islands in the bay of Bengal half way between India and Siam (modern day Thailand). Used in the solid for making more robust Colonial furniture for export to the West. Padouk also occurs in SE Asia and was much in demand for floor boards.

Pine:

Easily identified by everyone pine is widely distributed throughout Europe. Used for paneling rooms in the 18th century, sometimes showing attractive ‘knotting’. Often to be seen used in case furniture carcasses and drawer linings. Veneers adhere better to soft and porous pine and are the preferred secondary woods for early veneered items such as walnut.

Satinwood:

Comes from either Ceylon and SE Asia or from the West Indies. Used mainly as veneers in the 18th century, later the East Indian variety was used in the solid for Colonial more robust items for export. Period 18th century satinwood veneered furniture is generally of light proportions and highly desirable when patinated and sometimes even painted. Very much encountered on pembroke tables and secretaires both in England and Europe.

Teak:

A rather undistinguished wood with regard to furniture. Much Colonial teak furniture was imported into the West in the 19th century mainly in the form of brass bound Military chests and bureaux. Teak was of course much favoured by shipbuilders for hulls and decks. The natural oils in teak were very effective in combating rot and worm in sea going vessels.

Walnut:

Introduced into England in the 16th century but little used for furniture at that period, mainly in chair making, until the early 17th century. The early years of the 18th century were sometimes referred to as the ‘age of walnut’ much in favour in the reign of Queen Anne in particular. Used by cabinet makers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries often in the form of veneers. With the arrival of the first mahogany imports in around 1720 walnut became a little out of fashion but even so was much used in country furniture. Walnut is reasonably hard and can patinate and fade into glorious shades of brown. Burr walnut is usually cut into veneers and oyster cut across the boughs. Colour and patina are everything when assessing walnut period furniture.

This photo shows an English antique walnut lowboy from about 1760.

Yew:

A familiar tree encountered in England. Native to central and southern Europe, north west Africa, and N Persia. An evergreen hard, insect resistant tree. In early times much used in ‘windsor’ chair stretchers and hoop splats due to its pliable nature.

Sometimes encountered in graveyards due to its toxic effects on livestock, farmers were careful not to let livestock stray! Yew is particularly toxic to horses. Also used in constructing the all important ‘longbow’ in English medieval warfare, there were restrictions to cut yew in the middle ages. Oldest weapon is an axe head possibly 450,000 years old. There was much international trade in prized yew wood until the advent of the gun.

Yew is very slow growing and can live for 2000 years plus. Yew was a symbol of longevity and planted in ancient times near Neolithic temples.

Veneered yew furniture is highly regarded and costly as is anything constructed in solid yew.

Here is a photo of a centuries old yew tree.